Efficient and accurate input of address information is essential for applications in e-commerce, food delivery, ridesharing, and more. Yet one small detail in the address form continues to pose challenges for users and developers alike: the Apt/Unit field. This optional data point—typically a suite, apartment number, or unit—is crucial for accurate deliveries but suffers from inconsistent input patterns, insufficient autocomplete support, and cumbersome mobile keyboard design.

The intersection of mobile input behavior and the ways servers handle address autocomplete leads to problems that frustrate users and diminish the credibility of address-based services. This article explores how input patterns for the Apt/Unit field interact with mobile keyboard behaviors and autocomplete APIs, and offers guidance on how to build more intuitive and successful user experiences.

1. The Nature of the Apt/Unit Field

The Apt/Unit input field is commonly used to denote a secondary address component. In the United States, for instance, an address might appear as:

123 Main Street Apt 4B New York, NY 10001

However, international variation in address formats, as well as user tendencies to input addresses in a single line using predictive keyboards, often causes overlap or omission of the apartment field. When users interact with mobile keyboards—especially those offering aggressive autofill or predictive typing—the fields can prefill inaccurately or become corrupted entirely. This matters especially when packages are left undelivered because the apartment number went missing during the form submission process.

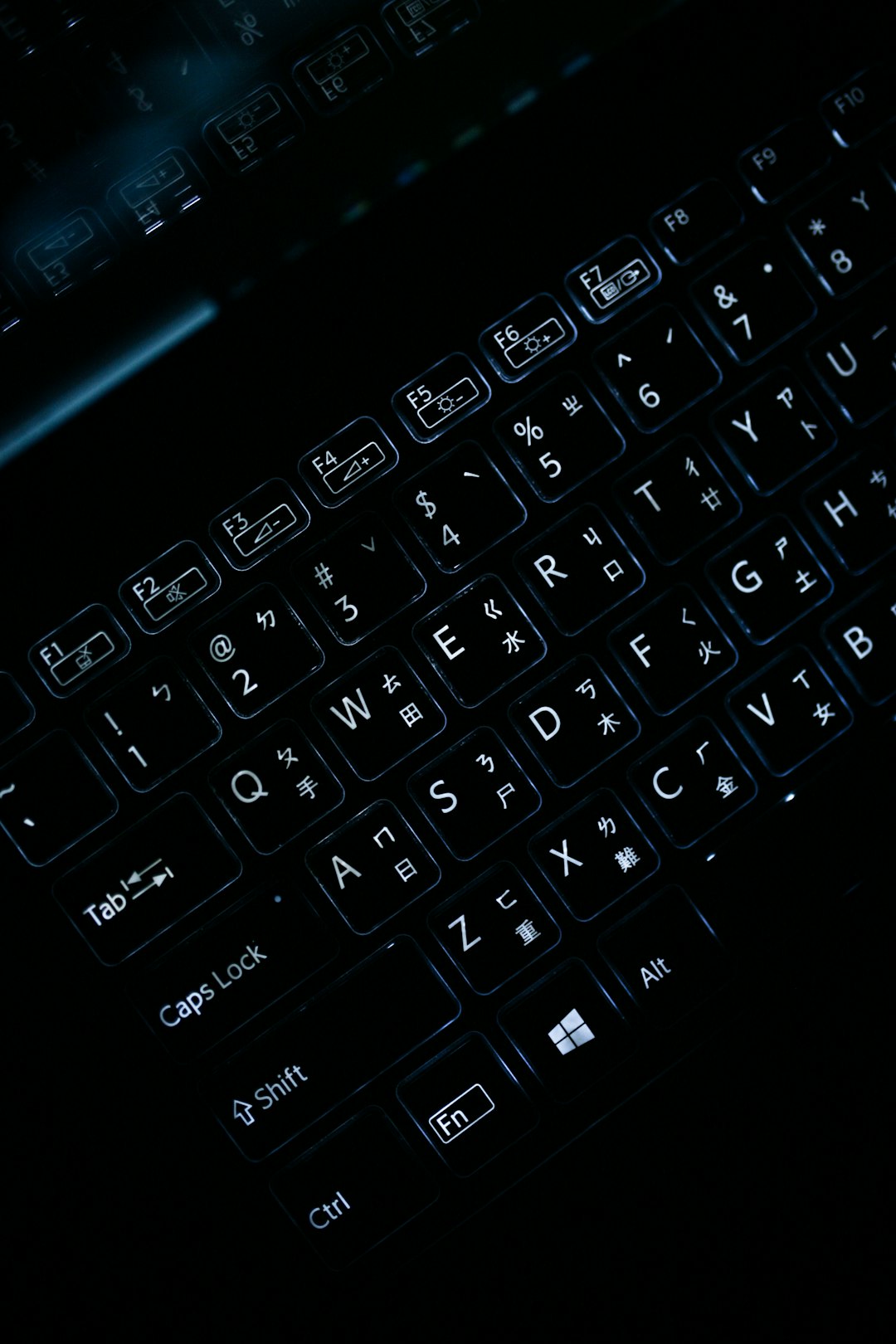

2. Human Behavior & Mobile Keyboards

Mobile keyboards are optimized for speed and convenience, often with custom predictive text, emoji suggestions, and saved entries. This works well for short messages or emails but less so for structured form input. Consider these key behavioral patterns:

- Single-line Entry: Many users will paste or type an entire address into one field, especially if autofill has stored a complete version. This often leads to the apartment number being merged into the street address field.

- Inconsistent Label Recognition: Because different websites use different terms—Apt, Unit, Suite, #, Room—it confuses users, making them unsure where to input their sub-address component.

- Language and Format Differences: Non-English speakers or travelers may use formats unfamiliar to local APIs, increasing the risk of data fragmentation.

Mobile keyboards generally offer autocomplete suggestions based on user behavior. As such, a previously entered “123 Main St Apt 4B” may continue to be offered as a single-line suggestion, regardless of whether the “Apt” field exists separately in the user interface.

3. How Autocomplete APIs Handle Sub-addresses

Modern address autocomplete services (Google Places API, Mapbox, HERE, etc.) focus primarily on street-level addresses. Some offer place-level granularity (e.g., office buildings or apartment complexes). Unfortunately, almost none support apartment number prediction in their APIs. This results in an input gap: while forms are increasingly reliant on autocompletion for speed and data validation, they fall short at the unit-level detail.

Some of the limitations include:

- Lack of Sub-unit Data: APIs rarely return sub-unit information; users often have to manually append apartment numbers.

- Poor Parsing of Appended Data: When a user pastes an address with an “Apt” suffix into a single input field, APIs sometimes misinterpret and discard it.

- Form Misalignment: Developers sometimes place auto-fill logic only on the main address field but neglect triggering it for associated fields, like Apt or Unit.

These issues are exacerbated on mobile devices, where screen real estate limits the use of multiple input fields and encourages single-line entry. This leads to a trade-off between speed and accuracy, often tipping in favor of user convenience over data integrity.

4. Design Patterns That Work

To mitigate these issues, thoughtful design of address forms and adaptive keyboard use is essential. Below are some strategies supported by real-world testing:

Use Distinct Input Fields but Provide Intelligent Parsing

Use a separate input field labeled clearly as “Apt, Suite, Unit, etc.” Displaying placeholder examples like “e.g. Apt 4B” educates users. However, back up this structure with parsing logic: if a user pastes “123 Main St Apt 4B”, the form should intelligently route each portion to the correct field.

Mobile Keyboard Optimization

Use HTML input types to assist mobile users:

- type=”text” inputmode=”text”: Use this for apartment fields to avoid numeric-only keyboards if alphanumeric labels are common (e.g., Apt 4B).

- Autocomplete attributes: Set

autocomplete="address-line2"on the Apt/Unit field. Additionally, correctly tag the main field asautocomplete="address-line1"to ensure proper browser-level address suggestions.

Autocomplete That Defers to User Input

When autocomplete is implemented, it should populate only the fields it’s confident about. Users should retain the ability to override or append information manually. An effective autocomplete interface lets the user confirm or reject specific portions of the suggestion, especially apartment numbers, rather than silently overwriting them.

5. Global Examples of Sub-address Complexity

International address structures vary significantly. Consider these examples:

- Japan: Addresses may follow a ward-block-house number structure, with no explicit equivalent of “Apt.”

- France: Apartments in older cities are sometimes defined by floor or specific building entrances, not unit numbers.

- India: “Flat,” “Tower,” and “Block” are used frequently—requiring custom handling in forms focused on Western formats.

This further complicates the case for a universal Apt/Unit pattern. Developers should consider region-specific placeholder text or dynamic UI that changes based on country selection. It may also be necessary to avoid rigid terminology by using a generic label like “Additional Address Info.”

6. Testing & Analytics

Insights into actual user behavior can be gathered through analytics tools designed for form interaction. Measure where users drop off during address input, detect pasted values, or flag repeated delivery failures originating from missing unit data.

Additionally, A/B testing form field arrangements (one address field vs. separate address and unit fields) can uncover performance differences. It’s valuable to track:

- Completion time

- Error correction rates

- Occurrence of delivery-related support tickets

These metrics help refine the optimal balance between mobile usability and form accuracy.

7. The Road Ahead

As digital commerce grows, particularly in mobile-first countries, the Apt/Unit field will become even more critical. Developers, UX designers, and API providers must collaborate to handle this input robustly. Some areas of opportunity include:

- Enhanced Parsing APIs: NLP-powered systems could parse user-entered addresses and automatically detect and segment apartment numbers.

- User Education: Small UX cues like explaining why unit information is essential could improve accuracy and user intent.

- Standardized Schemas: Encouragement of structured address formats across services (e.g., through government or postal standards) could normalize user behavior.

Conclusion

Though seemingly minor, the Apt/Unit field represents an unresolved edge case in mobile input and form design. Its challenges stem from inconsistent user behavior, limitations in mobile keyboard design, and incomplete integration with autocomplete APIs. By recognizing the behavioral and technical nuances of sub-address input, developers can make systems more reliable and user-friendly—leading to fewer delivery errors, lower costs, and higher customer satisfaction.